From the Archives

Did you know that for about half a decade in the 1940s, Oglethorpe had a medical school? Did you know that we enrolled two women into our medical program — two years before Emory Medical School and four years before Harvard Medical School?

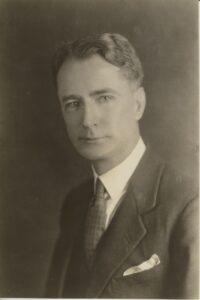

In 1941, OU President Thornwell Jacobs established a medical school in order to educate doctors to help reduce the dearth of medical professionals as war loomed in Europe. He received initial support from the Georgia State Board of Medical Examiners and appointed his son John L. Jacobs as vice president in charge of establishing the program. The younger Jacobs had earned undergraduate degrees from Oglethorpe and Harvard before earning his medical degree from Harvard.

In the first class that enrolled in September 1941, there were about fifty students from as far away as Puerto Rico. In fact, about 10% of incoming students were from Puerto Rico—around the same proportion of students from Georgia. Two women were in the inaugural class. Emory Medical School would not accept its first woman into its program for another two years and Harvard Medical School not until 1945.

At OU, first year medical students, or “medicos” as we called them, enrolled in courses like anatomy, biochemistry and physiology. Second year students took pharmacology, pathology and bacteriology. Medical school tuition at Oglethorpe was $930 per year (about $21,000 today) which was over twice as much as Emory.

In 1941, several elephants were poisoned during a visit to Atlanta by the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus. Dr. John Barnard, professor of anatomy, arranged for one of the elephants named Palm to be brought to campus and dissected by one of his classes. After the dissection was complete, students dug a grave behind Lowry Hall and buried Palm. Parts of the expansion of Lowry Hall into the Philip Weltner Library in the early 1990s is located over the grave.

Jacobs planned for OU students to receive clinical privileges at Grady Hospital after completing two years of intense, classroom instruction on campus. At that time, Emory’s medical school enjoyed exclusive opportunities there. Grady stated the denial of privileges was due to the lack of accreditation of the program by the American Medical Association, but Oglethorpe officials felt Emory was using its influence to squeeze them out of the Atlanta medial school market. After this defeat, Jacobs decided to establish a clinic for African Americans in downtown Atlanta to be staffed by OU medical students. In 1943, the Atlanta Board of Zoning Appeals approved the site pending a remodel to ensure the building was fire resistant, but it never came to fruition.

By this time, the lack of clinical privileges as well as the negative publicity generated by the public battle for Grady Hospital permission, the Oglethorpe University Medical School closed. Philip Weltner, OU president after Jacobs’ resignation, found other medical programs for each OU student to transfer to. It would be three decades before OU established another graduate program.